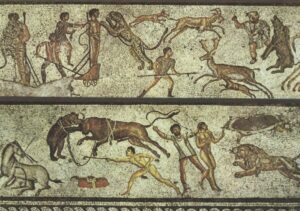

Analysis of a human skeleton from what is a believed to be a cemetery for gladiators from Roman York shows bite marks on the bones of one individual, known as . This strongly suggests the gladiator was picked up and carried in the jaws of a lion – likely after the lion had killed or wounded him in the arena.

This is the conclusion of an article entitled “Unique osteological evidence for human-animal gladiatorial combat in Roman Britain,” in the journal Plos One from April 2025. (Linked from the article title above.)

This is significant because it’s the best evidence yet for big cats in Roman Britain. It’s surprising because it would cost a lot of money and effort to bring a lion all the way over from Africa or Eastern Turkey or the Middle East (the extent of the lion’s range at the time) to the city of Eboracum (York), not even the capital of a far flung province of the Empire. Venatores were specialists attached to the Roman army tasked with capturing exotic animals for the circus, or more mundane game animals on which t feed the troops.

Some believe that today’s British big cats have their origins in a tiny relict population of surviving big cats let loose or escaped from gladiatorial arenas, augmented over time by escapes from menageries and circuses before their population exploded following releases from private zoos after the Dangerous Wild Animals Act came into force in the 1970s.

There are a number of problems with this. Firstly, lions are creatures of the open savannah, not adapted for life in the British countryside as leopards, pumas and lynxes are. When lions do escape in the UK, they are usually captured or shot within a few days. This doesn’t exclude the possibility that there were leopards in Roman British circuses too, who would have fared better in the wild in Roman Britain. (Leopard remains were found in a Roman rubbish dump in Rome and in a Roman army camp in present day Romania.)

But the big cats brought over at great cost to Britain were brought to be slaughtered in front of a crowd. While the lion in York seems to have survived long enough to pick up and briefly carry off a gladiator, its life expectancy in the arena wouldn’t have been great.

Long before the Roman Empire collapsed, big cats and other exotics were in short supply for the arena. The demand for elephants and big cats for combat in the arena had stripped North Africa of these species. Accounts of late Roman Empire circus spectacles include staged hunts of herds of deer in the arena, presumably because big cats and elephants were getting rarer and harder to source. (Gladiatorial combat between humans fell out of fashion with the adoption of Christianity, but the spectacular slaughter of animals in the arena continued right up to Empire’s end.)

As Roman territory shrank, sourcing big cats and shipping them to the frequently rebellious province of Britain – sometimes out of Roman control entirely and ruled by local usurpers – became even harder. Big cats being around at the end of Roman Britain and then let loose seems less and less likely, given all these factors.

See here for earlier evidence of a caracal exotic wildcat in Roman Norfolk, and for more on evidence (or the lack of it) for big cats in Roman Britain.