- The following extract from Mystery Animals of Suffolk appeared in Fortean Times.

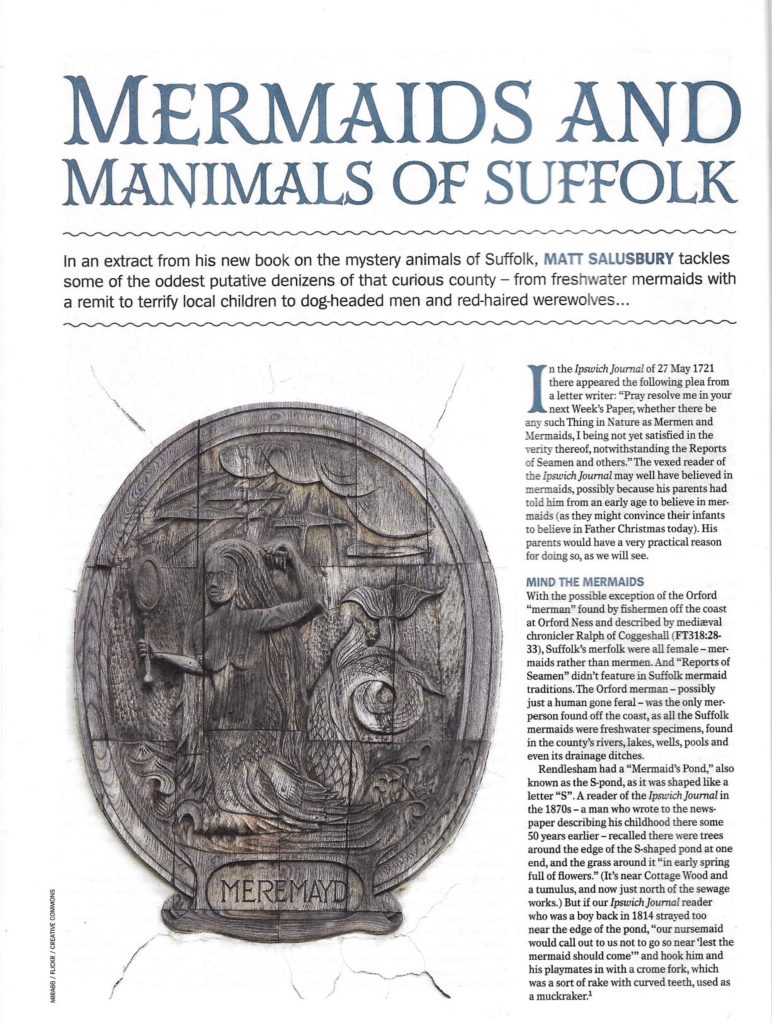

“PRAY resolve me in your next Week’s Paper, whether there be any such Thing in Nature as Mermen and Mermaids, I being not yet satisfied in the verity thereof, notwithstanding the Reports of Seamen and others.” That was the plea from a letter writer to the Ipswich Journal, 27 May 1721. The vexed reader of the Ipswich Journal may well have believed in mermaids, possibly because his parents had told him from an early age to believe in mermaids (as they might convince their infants to believe in Father Christmas today). His parents would have a very practical reason for doing so, as we will see.

With the possible exception of the Orford “merman” found by fishermen off the coast at Orford Ness and described by medieval chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall, Suffolk’s merfolk were all female – mermaids rather than mermen. And “Reports of Seamen” didn’t feature in Suffolk mermaid traditions. The Orford merman – possibly just a human gone feral – was the only merperson found off the coast, as all the Suffolk mermaids were freshwater mermaids, found in the county’s rivers, lakes, wells, pools and even its drainage ditches.

Rendlesham had a “Mermaid’s Pond,” also known as the S-pond, as it was shaped like a letter “S”. A reader of the Ipswich Journal in the 1870s – a man who wrote to the newspaper describing his childhood there some 50 years earlier – recalled there were trees around the edge of the S-shaped pond at one end, and the grass around it “in early spring full of flowers.” (It’s near Cottage Wood and a tumulus, and now just north of the sewage works.) But if our Ipswich Journal reader who was a boy back in 1814 strayed too near the edge of the pond, “our nursemaid would call out to us not to go so near ‘lest the mermaid should come’” and hook him and his playmates in with a crome fork, which was a sort of rake with curved teeth, used as a muckraker. (“Suffolk Notes & Queries”, Ipswich Journal 1877, quoted by the Fairy Investigation Society website.)

This figure on a shopfront in the Suffolk town of Woodbridge, a port on the River Deben, dates from the 1660s. It could be a melusine, a twin-tailed mermaid said to live in fresh water. The twin tails are on either side of her torso, with the tips of the flukes of her fishy tails pointing outwards.

The “S-Pond” at Rendlesham today, on the western edge of Cottage Wood. Photo: copyright Google Maps.

The “S-Pond” at Rendlesham today, on the western edge of Cottage Wood. Photo: copyright Google Maps.

The author of The Book of Days wrote in the 1860s how he was told by one Suffolk child that mermaids were “them nasty things what crome you into the water,” while another child from the county told him he’d actually seen a mermaid once, “a grit hig thing loike a feesh.” Kate Welham of Bacton, near Stowmarket, recalled being told as a child in around 1908 to stay away from mermaid-infested ponds. (The Book of Days, R. Chambers, W & R Chambers, 1863-4; Paranormal Suffolk: True Ghost Stories, Christopher Reeve, Amberley, Stroud 2009.)

Just outside Bury St Edmunds in Babwell Fen Meadows, once the private fishing lake of the Abbot of St Edmundsbury, there were in the mid-nineteenth century “an abundance of beautiful water” fed by springs, and in “the low grounds” near the road. (This is probably what’s now the Fornham Road.) A mermaid was to be found in the body of water then known as the Mermaid’s Pits. They were named after a “love-sick maid” who had drowned herself there, and who then turned into a mermaid; whether or not she was an evil mermaid who pulled in children wasn’t known, but there was supposed to be an “abundance” of mermaids in the drainage ditches and ponds locally. Local mothers warned their children to stay away from these. There’s now a Mermaid Close here, just off the Fornham Road, with a small body of water nearby. (A Handbook of Bury St. Edmunds, Samuel Tymms, F. Lankester, 1859. Alex McWhirter, Heritage Officer for West Suffolk, said his enquiries on the Mermaid’s Pits on my behalf had “drawn a blank.”

Pub sign for The Mermaid pub on Ipswich’s London Road, on the banks of the River Gipping.

A look at Google Earth shows some features round there that appear on older maps as pools but have now been drained. Some of the Mermaid’s Pits may have fallen on hard times, ending up as the settling ponds at what’s now the Silver Spoon factory. It was previously the British Sugar factory, manufacturing raw sugar from sugar beet in a process that involved washing the beets in a lot of water, which had to end up somewhere. For this reason, sugar factories tended to be built near where there was a ready supply of water. The smell of sugar beet tended to attract coypus, and the East Anglian sugar factory settling ponds usually had a “terrible smell” attached to them, according to a source who worked in other East Anglian sugar plants back in the 1970s. You can still see the silos of the Bury Silver Spoon plant as a landmark near the station, with big piles of sugar beet often stacked nearby. In any event, these settling ponds today would be no place fit for a freshwater mermaid to lurk, however evil.

The Silver Spoon sugar factory in Bury St Edmunds, along the Fornham Road. At the top of the photo are the settling ponds for the factory that could be the ancient “Mermaid Pits,” also known as the “Merry Maid Pits.”

The Silver Spoon sugar factory in Bury St Edmunds, along the Fornham Road. At the top of the photo are the settling ponds for the factory that could be the ancient “Mermaid Pits,” also known as the “Merry Maid Pits.”

A short distance from Bury St Edmunds, on the River Lark at Fornham All Saints and just a little bit further upriver at Hengrave, there was said to be a mermaid, either in the river or in the well. The mermaid – apparently without the use of a curved rake – would grab and drown children who ventured too close or even touched the water. There was also a phantom woman on a horse who was seen to ride across the surface of the nearby mere (lake) on certain days of the year. The ghost story writer MR James grew up nearby, at Great Livermere, and penned many a short story about “antiquarians” researching the more peculiar corners of forgotten Suffolk history and archaeology and ending up meeting a sticky end at the hands of some ancient malevolent East Anglian entity that they’d stirred up. The area around Fornham All Saints, with its massive Neolithic and Bronze Age monument (now threatened by housing development) inspired James’s ominously-titled ghost story A Warning to the Curious. (Alan Murdie, “Ghostwatch”, Fortean Times FT 325;18, March 2015, quoting “Folklore from S.E. Suffolk”, Lady E. C. Gurdon, Folklore, December 1892.)

The people of the fens were thought (by others) to have some fairy or mermaid blood in them, or were believed to be born web-footed. The “half-mermaid” fen-dweller girls in particular were feared. It was whispered of them that they loved to play near pools and dykes and push their normal playmates in.

There was yet another freshwater mermaid said to live somewhere in Suffolk’s River Gipping at some unknown point in history. The mermaid that frequented the Gipping would prey on children who played near the deeper waters of the river. Then there’s The Mermaid pub on the banks of the River Gipping, the old Stowmarket Navigation canal at the point where the London Road crosses it in Ipswich, just before it comes out into the Orwell. As it wasn’t clear exactly where the mermaid was to be found, it was wise for children to stay away from the Gipping altogether. (The entity in Wimbell Pond near Acton (just east of Long Melford) may or may not have been a mermaid. A chest of money is said to lie at the bottom of the pond. Those who have thrown stones into the pond have heard it make a ringing noise as it strikes the chest, and seen a small white figure whimpering, “That’s mine.” (The Folklore of East Anglia, Enid Porter, BT Batsford, London 1974; Paranormal Database.)

Mermaids tempt seamen away from drink and into the Sailors’ Reading Room in the Suffolk seaside town of Southwold. Suffolk’s evil freshwater mermaids, however, are a freshwater phenomenon and there are no tales of them along Suffolk’s coast.

Mermaids tempt seamen away from drink and into the Sailors’ Reading Room in the Suffolk seaside town of Southwold. Suffolk’s evil freshwater mermaids, however, are a freshwater phenomenon and there are no tales of them along Suffolk’s coast.

You’ve probably already guessed the perfectly rational explanation for all of Suffolk’s freshwater mermaids. Until recently, Suffolk children were expected to be out of the house and out and about all day, and not expected to show up again until teatime. The temptation to play – unsupervised – near ponds, lakes, drainage ditches, rivers and meres was great. Parents made up stories about absolutely lethal and terrifying mermaids living in these bodies of water in an attempt to keep their children away from them. In other parts of England, there were witches instead of mermaids living in wells.

Ginger werewolf of the East of England coast

Via Nick Redfern comes a story “passed down from generation to generation from a family in Kent”, about the Shirley family, who were picnicking in “an area of woodland” on the East Coast of England sometime at the end of the 1940s. Pat Shirley had been told the story by her grandfather, who was there, but she wouldn’t tell Redfern where the incident had happened (or possibly by the time the story had been passed down to her, the location had been forgotten).

Pat Shirley’s grandfather told her that during their woodland picnic somewhere on the East Coast, he’d caught the briefest of glimpses of a werewolf-like manbeast “covered in flaming red hair” and “possessing a pair of huge and powerful jaws.” It then vanished into the trees. (“The Werewolves of Britain” Nick Redfern, FATE magazine, March 2006; Cryptomundo website)

A look at an atlas shows that wooded stretches of the East of England coast – from the Thames Estuary in Essex and all the way up to Lincolnshire – are limited. There’s nothing very much going on by way of noticeable woodland near the coast anywhere in Essex. Nor is there anything noteworthy by way of woodlands on the Lincolnshire coast either. So a wooded stretch of coast in the East of England would probably be in Norfolk or Suffolk. Some stretches of the Suffolk coast with woodland nearby do spring to mind – around Sizewell, along the Dunwich coast as far as Dingle, and if you strayed inland from Walberswick beach you’d find yourself along some farm tracks and bridleways lined with dense avenues of trees on both sides. Benacre and Covehithe have woods close to the shore, and right behind Aldeburgh (away from the beach) there are woods.

I don’t pretend to be an expert on North Norfolk, but the Norfolk seaside resort of Sheringham to this day advertises itself as “twixt sea and pine”, with pine forests near the beach. Maps suggest that areas behind the North Norfolk beaches of Horsey, Stalham, Holkham Bay and Hunstanton also have some woodlands.

That’s the state of our East of England wooded coastline today, but what about in the 1940s? There may well be some little wooded stretches of the shore that have simply fallen into the sea since then, through coastal erosion. I recall that when I was a child, in the 1970s, there were trees at the top of the cliffs at Dunwich and at Iken Cliff with ropes hanging from their branches for children to swing on, and roots to clamber over, and these are both long gone. The great fallen trees that lie on their sides on the beach at Covehithe are all that remains of what was once a wood at nearby Benacre, lost to coastal erosion and floods in recent times. I invite readers to peruse large-scale 1940s maps of the East and England coast to pinpoint the location of an incident that I find it hard to believe could have happened in the first place.

The dog-headed man of Tuddenham

Tuddenham St Martin, just north of Ipswich, is home to the Magpies, Ipswich’s rugby club. Local business Tuddenham Hall Foods is England’s biggest asparagus grower. In Tuddenham St Martin, in the 1980s and 1990s, there was “a tradition of sorts” of a local “dog-headed man” that would “seem to be passed down from older brothers and fathers in that area,” according to Chris Field, who as a child moved into the village.

Is this a dog-headed man on the roof of All Saint’s Church, Blythburgh, “The Cathedral of the Marshes”? Or is it a bear?

Chris told me a friend’s dad had “told us a few things” about the dog-headed man, possibly while “trying to put the scares on us.” To this day he’s unsure as to whether the dog-headed man of Tuddenham was supposed to be “a spirit creature” or what, exactly, it was supposed to be. He did tell me there were “tales of a man with a wolf’s head in the area” and that these were “linked to certain locations, bridges and river ways.” Chris admitted that in the area around Tuddenham, some of the woodlands “do have a certain energy… the feeling like you’re being watched, copses that make you feel unwelcome.”

These were often the places locally where Tuddenham youths would play “manhunt” or “it”, games no doubt made more exciting by the prospect of the dog-headed man lurking behind you in your hiding place! (Chris Field, telephone interview, 9 September 2015. There is a Dog’s Head Street in the centre of Ipswich, this apparently has its origin in the pub sign of a medieval Flemish inn that once stood there.)

Something like the dog-headed man of Tuddenham may have wandered 16 miles northeast to terrify two teenage boys. A Suffolk informant (we’ll call him “Paul”) described being stalked by something one summer night in 1995 while “wild camping”. The noises it made while “stomping around”, and the sounds of branches breaking on the forest floor, made Paul feel that it that walked on two legs, although he didn’t get a look at it.

This incident took place in Dodds Wood, near Sweffling, on the Glemham Estate. “Paul” and a friend spent their teenage years “roughing it” in unofficial campsites. In the summer of ’95, the two friends built one of these camps with a fire pit in Dodds Wood. Paul and friend stayed up most of the night after hearing something walking around the edge of their camp. The “stomping” and “branches breaking” came closer until an hour before dawn”, when the noises finally receded.

The boys returned the next night, with Paul’s dad’s dog. The noises resumed. When the dog “started going berserk and barking like mad… whatever it was… ran off very fast and we could hear the branches breaking as it ran.” Days later, during a thunderstorm, Paul heard a “huge howl that went on for more than half a minute,” which came from the friends’ camp area. (“Paul”, Pers. Comm. by email, 30 September 2015)

Some of Suffolk’s demi-humans were just stories made up to scare kids, others – while obviously impossible – have nonetheless been encountered by sane adults in disturbingly recent times.

Dog’s Head Street in the centre of Ipswich, Suffolk’s county town, commemorates the name a Flemish pub that once stood in the street.

Matt Salusbury is the author of Mystery Animals of Suffolk – including an account of over 150 mystery big cat sightings from which this is an extract. The book’s available via its distributor Bittern Books or via bigcatsofsuffolk.com. Matt is also Chair of Dunwich Museum and a regular FT contributor.

Copyright Matt Salusbury, 2023, 2024. For reasons of copyright, some of the illustrations are different to those in the Fortean Times article.

Merpersons (with wings!) on the panelling at Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich.

Merpersons (with wings!) on the panelling at Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich.

I was interviewed on Mystery Animals of Suffolk on Rick Palmer’s excellent Some Other Sphere podcast. We covered East Anglian wildmen and their origins, the Stowmarket cluster of fairies, Black Shuck, the Rendlesham UFO Incident, evil freshwater mermaids and finally Suffolk big cats, among other subjects.

I was interviewed on Mystery Animals of Suffolk on Rick Palmer’s excellent Some Other Sphere podcast. We covered East Anglian wildmen and their origins, the Stowmarket cluster of fairies, Black Shuck, the Rendlesham UFO Incident, evil freshwater mermaids and finally Suffolk big cats, among other subjects.